Perpetual Calendar

Peggy Kamuf

1. When Nietzsche describes, in The Genealogy of Morals, how "to breed an animal with the right to make promises," without saying say so he was talking as well about the invention of the calendar (from calendae, or kalendae, the calends, the first day of the Roman month, when debts fall due; calendarium or kalendarium: an account-book). For man "must have become not only calculating but himself calculable, regular even to his own perception, if he is to stand pledge for his own future as a guarantor does" (Second Essay, I). The promising animal had to invent the calendar, start keeping a calendar that could stand pledge, as a guarantor does, for debts and dates: dates (from datus, given) incur debts or the other way around.

2. Memory counts, calculates, calendarizes. It keeps a calendar so that it may keep its dates or keep up its payments. It keeps the calendar, but the calendar also keeps memory, keeps it safe or as safe as possible from loss, from losing the memory of itself, the memory of memory. The calendar keeps memory safe for, if not already in the future. This invention, or discovery, is no less an invention of "man," objective genitive. Man is invented, "he" is also a technical invention of this thing called a calendar.

3. So what is a calendar? Is there any such thing? Is it a thing? Or a concept? Is there a clearly defined concept of "calendar"?

4. The calendar is the guarantor of memory's future, its faithfulness to its pledge, made here and now in the present but, of course, in the future this present will be past, the largely irretrievable, forgotten past into which the pledge, the promise can disappear unless it is kept safe, guaranteed, warranted by the calendar, by something called a calendar (whether a daily agenda book, a wall calendar, the program in a palm pilot). A calendar can also be something, and in fact many sorts of things on which to write or make iterable marks, marks that can be read and deciphered at some future date.

5. But as itself a set of iterable, decipherable marks, a calendar is also something written. Any concept of "calendar" would have to presume this trait, the trait of writing or iterability. The calendar marks and counts repetitions because it is itself a set of iterable marks, which can be "read," that is, iterated, repeated as both sameness and difference. To keep a calendar is to keep the iterable trace indefinitely back into the past or forward into the future.

Indefinitely, perhaps perpetually.

6. A perpetual calendar, now, is that something, or is it "just" a concept, an idea, perhaps a desire, a wish, a fantasy, a fiction, or phantasm?

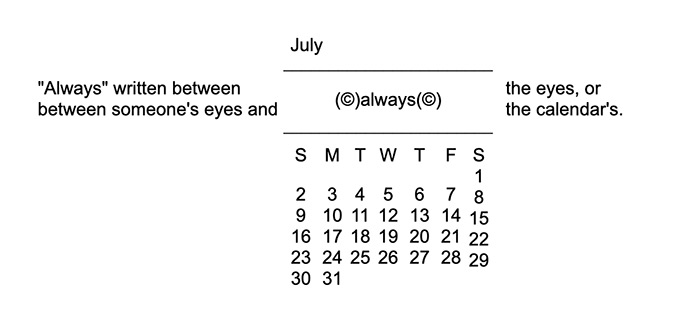

Here in front of me a plastic thing of moveable parts. I've had it for many years (a birthday present?), and so far it has never failed as a bare calendar, that is, as the mere grid of interlocking days and the numbers from 1 to 31. Its clever design is copyrighted on the back: "The Always© Calendar". One cannot write on it, at least I never do and no one else ever has. It merely recalls the matrix of days and dates (let's see, if today's Monday, it must be the 12th), to keep one from writing the wrong date some place else, for example, in a letter or an e-mail. Its surfaces are not for writing, but it is an aid to writing on some other surface. I keep The Always© calendar current every month, so this little mnemotechnic tool writes and remembers faithfully, provided I move its pieces around, the dates of every month of every year that has ever been or will ever be, could ever be lived, including but not just all the months I have lived with it, so far.

7. All the possible dates of a life-mine, all the others'-already always written there.

8. Probably no one would spontaneously call it beautiful. Still, it functions beautifully with its strict black and white contrasts, in clear, hard writing, its letters and numbers easy to read, even in a darkened room, before the lights are turned on, morning or evening. It is a tool, but a tool in service of the calendar concept, that is, the perpetual (or Always©) calendar.

When I think about it and begin to calculate, I can see no reason to believe it will not last the rest of my life. I should never need another calendar on my desk, so for me, it will have been true that it was "perpetual." Or at least I will have seen it into perpetuity, and I can affirm that it was, is, will have been perpetuable if not in fact perpetual.

9. Especially after the word always, always after the word always, is where, today, I most want to sign this perpetual calendar of the life lived under its eyes. For the calendar has eyes, it seems (I'm just discovering this myself) or at least it has me and "my life" in its view, if not perpetually, then I may hope always(©). Always(©), parentheses added, not the copyright but the signature, the co-signature of the guarantor of "my life."

10. Where else to sign but after a word like always? Or before it? After or before, the one always(©) always implies the other: (©)always(©). Imagine it written at the height of what would be the eyes if its square form were a face. Something like this:

11. Perpetual: from perpetuus, uninterrupted, continuous, lasting, universal, constant; in perpetuum (words of the Requiem mass), for ever (and ever). First definition of perpetual, OED: "Lasting or destined to last for ever; eternal, unceasing; permanent (during life)." Ah, yes: during life.

12. (Note for "PC" essay: The Internet as perpetual calendar and perpetual clock. Never have to write the date or time in e-mails, they are automatically inserted. Every PC functions as perpetual calendar, giving unlimited support to marks that have to be remembered. The PC keeps time, memory, dates, debts, calendars, address books, phone numbers, fax logs, mailboxes, everything. Mnemotechnology: continuous, uninterrupted, perpetuating. Technobiomnemonics: Perpetuated reinvention of the calendar.)

13. Other sorts of calendars I use, besides (©)always(©). There is the date book or agenda, bought in Paris every year. Always a Quo Vadis ("©Copyright QUO VADIS" on the first page). (Remember to get a new one next month.) The address book in the back pulls out to be reinserted in each year's new agenda. A different cover every time (currently it is red leather, and I like it especially). When the address book gets too worn, it has to be recopied. The French calendar printed in the week-by-week "planning" section includes all sorts of information. For example, each day's patron saint (St. Clotilde on June 4th, St. Kévin on June 3rd). One can also read how many days have past in the year and how many are left: on June 4th, 155 days have past and 210 remain. The weeks are also counted (this is the 22nd ). One may easily find which day is the numerical halfway point of the year. I just discovered this day does not, as roughly calculated, fall halfway through July, the 7th month. The midpoint occurs on the 1st of July, which is the 183rd day of the year, with 183 days remaining. And in case you were wondering, St. Thierry presides as the year turns toward its end.

14. On the 14th day of the 7th month, during the 28th week of the year, 196 days will have past and (only) 170 will remain.

The days are not just counted but expired, expiring. "Your days are numbered," it says. A would-be perpetual calendar like (©)always(©), of course, records or announces no such statistics, not even the year. On the contrary, it differentiates minimally among the days in order to remain current. It is (©)always(©) current, unlike Quo Vadis, which expires and which can be thrown away if one is not sentimental about such things.

A perpetual calendar, if there could ever be such a thing, would know how to recall the days without counting.

But let's finish the inventory. I usually hang a wall calendar in the kitchen, which gets changed every year. These are large, can be read without glasses, and I sometimes write on them. This year's is the L.A. Times garden calendar, a gift from my neighbor Judy. There's pleasure in turning the pages once a month (I rarely look ahead) and uncovering another image. I have also another, smaller wall calendar in my office at school; for the last few years it has been the Amnesty International calendar, which I receive as a kind of gift from that organization. It hangs in such a way that students can see it behind me over my right shoulder as I sit across from them at my desk. (Only once has a student mentioned it, and then it led to a good conversation.)

There, that is the inventory of most of my calendars, at least in the conventional sense. A complete inventory would have to include all sorts of electronic calendars which I and millions of others use without even thinking about it. Besides the computer's calendar (which is right now ticking off the minutes in the lower right corner of the screen), there are the calendars or dating systems of fax machines, VCR's, televisions (broadcast programming or scheduling makes them, along with the Internet, into a powerfully regulating calendar), microwaves, answering machines, and the telephone itself, on which I may at anytime dial up the date and exact time of day. And then there are all the palm pilots, cell phones, remote connections of different sorts.

In other words, as extended by the technological web, calendars or the calendar is everywhere, impossible to inventory. Automatically, silently, invisibly, it goes on imprinting date and time, year and month, without interruption.

(But not without potential error: Y2K anxiety was perhaps merely the belated reaction to this condition in which the calendar is kept not by man alone but also and automatically by a machine or by technology-a very belated reaction therefore, since man never "owned" the calendar to begin with, no matter how often it has been copyrighted. What is more, the Y2K episode staged the calendar's betrayal of human memory when it becomes the guarantor not of the pledge to remember but of forgetting, a whole millennium forgotten. It betrays that memory to itself as well, that is, it shows it the limit of its own forgetfulness, of all that has and will be forgotten.)

But even more impossible to count off and classify would be all those other non-conventional, even singular calendars that anything is or can become, from the moment something is able to bear, and even to perpetuate, the iterable mark with which to recall innumerable days.

15. Anything at all, but beginning with a poem, or with poematicity. For today, then, a calendar-poem, by the calendar poet par excellence.

There is a Zone whose even Years

No Solstice interrupt-

Whose Sun constructs perpetual Noon

Whose perfect Seasons wait-Whose Summer set in Summer, till

The Centuries of June

And Centuries of August cease

And Consciousness-is Noon.

16. By searching pretty much at random, I found this use of "perpetual" after only 3 or 4 glances into the 1775 numbered poems (this is #1056).

"Perpetual" is certainly one of her words, as a concordance would confirm no doubt. But I say Emily Dickinson is the poet of the calendar par excellence not only because the themes or subjects of her poems are so often the astronomical year, the passage of days, seasons, lives, friends, flowers, and so forth. I also have this theory that an actual calendar year, 1862, got written into the oeuvre or had a hand in it, somehow, through a kind of ghost writing, if you will (and because the theory posits the action of ghosts, or at least spectrality, it will always be unverifiable). The year 1862 was the year in which she wrote 366 poems, virtually one every day, and it would have been an exact match if 1862 had been a leap year, which it was not. There was never a year like that again for the poet; after 1862, she wrote an average of 61.4 poems each year. Before that her "output" averaged 33.4 a year.

These calculations, by the way, have been made easily with the help of the table provided by the editor, Thomas Johnson, in an appendix to his edition of the complete poems. Having now consulted this table again, I have to tell you what I just found there: a surprising coincidence.

Among all the classifications of the poems, Johnson notes on this table how many exist in manuscript and for how many there is no autograph copy; he also differentiates among three different kinds of manuscript copies. By Johnson's count, of the 366 poems written in 1862, 196 of them exist in fair manuscript copies, while 170 exist only in semifinal drafts. Having never paid attention to this statistic before, I notice now for the first time a potentially pertinent fact for my theory regarding Dickinson's year of 1862. For a quick glance up and down the table reveals that 1862 is the only year for which we have only fair or semifinal copies of the poems, all 366 of them. There are no missing autograph copies and no manuscripts of poems in worksheet draft. This again sets this year apart as extraordinary.

But what is also extraordinary, at this moment and at least for me, is the strange coincidence of the paired figures 196/170 that had already begun, yesterday or the day before, to emit its signal from a certain page of this year's calendar, the page on which July 14, 2000 is noted to be the 196th day, with 170 remaining.

I won't try to make anything of this coincidence, but only because anything could be made of it. And whatever I "made of it," would have to be wrong, since it's quite obviously the other way around. "It" is making "me," and making me write, day by day, in the calendar, on the calendar. The calendar has dictated everything from the first word, the first perpetual word.

17. I have often wondered, of course: why 1862? Biographers, who all remark the extraordinary year, usually go for clues to ED's correspondence and "personal life," as it's called (in particular, to her relations with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who is the presumed addressee of the famous Master letters also written in 1862). Biographies can weave many threads from this material to try to close the gap of speculation with more or less coherent fictions, but these will always remain essentially unverifiable. I have not come across any suggestion that there might be an obvious or at least a more public explanation of 1862; it was, after all, one of the bloodiest years of the American Civil War. But since the poet said little in writing about the war, its mounting toll of days and dead, there is more or less general agreement among Dickinson scholars that one must discount such a public explanation. And from this evidence, or lack thereof, they forbid speculation among themselves about the poet's experience having anything to do with a year of war whose end was nowhere in sight in 1862.

The 366 ghosts of 1862.

18. [Here a typed page is inserted in the calendar:]

If one had infinite time, or at least the time of one leap year, one could show, I believe, that because each of the 366 poems of 1862 can be read according to an always indeterminate number of interpretive grids, because these are not overlaid in any symmetry of correspondence and thus cannot be lined up under any unified or unifying law, each poem is incalculably multiplied. This multiplicity raises the daily figure 366 by so many factors of years. It is, for example, almost always possible to read each poem as a prayer said over the remains of the dead, someone's dead, someone dead. To be sure, the incalculable number of poems written during the war years can always be read as addressed to God, beseeching charity for the dead and thereby for oneself whom so many dead are coming back to haunt and torment. This would be, if you will, the orthodox reading of Dickinson as poet practicing theology.

But such an interpretation is foremost a decision about the destination of address in this poetry. Destination can always be theologized. The horizon of address is thereby enclosed by the theological infinite, to which or to whom every prayer finally gets delivered through faith.

But every poem, if it is still a poem, reopens its address to another destination, always another possible destination, without end. It is address without destination, finite or infinite. Dickinson's perpetual calendar for the year 1862 is a finite infinitude, or, if one prefers, an infinite finitude of days, of poems, of poems that are also days and about days, of days that are also poems and about poetry, about the life or the living of poetry, without end. What we can still call life and living thanks to the poem's address.

19. The calendar, of which there is one and only one, is essentially theological. Outside the realm of pure belief, without reason, there are only calendars. Even the Internet, the most effective perpetual calendar for the world today in so many ways, is only "there" on innumerable screens, where the calendar is never exactly the same, never the same as itself. Always without itself, without end.

20. There are only calendars? Everything, anything is or may be a calendar? Yes, provided it marks a day or a date for someone. Anything at all, and anyone at all.

An example:

[Here two loose pages inserted from translation of "Typewriter Ribbon" by Jacques Derrida:]

Several weeks ago, in Picardy, a prodigious archive was exhumed and then deciphered. In layers of fauna and flora were found, protected in amber, some animal or other, some insect or other (which is nothing new) but also the intact cadaver of another insect surprised by death, in an instant, by a geological or geothermal catastrophe, at the moment at which it was sucking the blood of another insect, 54 million years before humans appeared on earth. 54 million years before humans appeared on earth, there was once upon a time an insect that died, its cadaver is still visible and intact, the cadaver of someone who was surprised by death at the instant it was sucking the blood of another! But it would suffice that it be but two hours before the appearance of any living being or other, of whoever would be capable of referring to this archive as such, that is, to the archive of a singular event at which this living being will not have been, itself, present, yesterday, an hour ago-or 54 million years before humans appeared, sooner or later, on earth.

It is one thing to know the sediments, rocks, plants that can be dated to a period when nothing human or even living signaled its presence on earth. It is another thing to refer to a singular event, to what took place one time, one time only, in a non-repeatable instant, like that animal surprised by catastrophe at the moment, at some instant, at some stigmatic point of time in which it was in the process of taking its pleasure sucking the blood of another animal, just as it could have taken it in some other way, moreover. For there is also a report of two midges immobilized in amber the color of honey when they were surprised by death as they made love: 54 million years before humans appeared on earth, a jouissance took place whose archive we preserve. We have there, set down, consigned to a support, protected by the body of an amber coffin, the trace, which is itself corporeal, of an event that took place only once and that, as one-time-only event, is not at all reducible to the permanence of elements from the same period that have endured through time and come down to us, for example, amber in general. There are many things on earth that have been there since 54 million years before humans. We can identify them and analyze them, but rarely in the form of the archive of a singular event and, what is more, of an event that happened to some living being, affecting an organized living being, already endowed with a kind of memory, with project, need, desire, pleasure, jouissance, and aptitude to retain traces.

I don't know why I am telling you this. . . .

Now, if this passage can be said to describe or inscribe an effective calendar, perhaps even a perpetual one, then one ought to be able to determine for whom it marks a date. That is, for whom does it recall something to be remembered (a date, a debt, a deadline)? For whom is it effective mnemotechnology? Well, certainly not for the insects, which are entombed with the thing's very existence. The only actors in or witnesses to the event who could recall it as something once experienced obviously cannot. Likewise, the event is not recalled to anyone else living because it happened entirely beyond the reach of anyone's memory or experience. This is Derrida's point, I think, when he repeats again the date of "54 million years before humans first appeared on earth" only to add: "But it would suffice that it be but two hours before the appearance of any living being or other, of whoever would be capable of referring to this archive as such, that is, to the archive of a singular event at which this living being will not have been, itself, present, yesterday, an hour ago-or 54 million years before humans appeared, sooner or later, on earth." It suffices, in other words, that one be absent from an event, to have missed it by nanoseconds or by 54 million years, to be unable to recall it to memory, one's "own" memory. This "calendar," therefore, cannot be anyone's, it cannot mark a date in anyone's memory, for past or future reference and recollection. In that is so, then in what sense would it still be a calendar at all?

I think Derrida responds in the passage we're trying to read. Without ever naming it or having it anywhere explicitly in mind, the calendar seems to get re-marked if not redefined here, most clearly in these terms: "We have there, set down, consigned to a support, protected by the body of an amber coffin, the trace, which is itself corporeal, of an event that took place only once and that, as one-time-only event, is not at all reducible to the permanence of elements from the same period that have endured through time and come down to us, for example, amber in general." This "calendar," newly defined, records the trace of events, of corporeal events, which both can and cannot be distinguished from their support. It is a trace of that which both is and is not the same thing as its support. An event is not a thing, no thing, yet it is traced, materially, on what we are still calling a calendar, which both is and is not the same thing as its support.

This new Derridean "calendar" does not count years or months; it supports the trace of an event and as such it is essentially nothing human, nothing of human invention. The new "calendar," the new, old calendar (at least 54 million+ years old and counting) is or bears, at least potentially, the trace of all events, as minuscule as the one preserved in amber or as cosmic as the bang.

(Not the calendar, but whatever, for example, a 54 million+ year-old piece of amber. Call it what you will, call it still if you like with that old Roman name recalling debt, guilt, bad actions. Will there ever be a name for a "calendar" that can forget or even forgive?)

I must confess something. Over the last day or so I have had to recognize that this 54 million+ year-old "calendar" or calendar effect may once again be from my own inventory, and thus it would be for me, perhaps only for me, that it is functioning first of all as such. I now believe that by citing the passage preserved in amber I wanted to recall hearing you, Jacques, read those sentences for the first time to your seminar in Paris, it must have been 1998, which was for me the year of Paris VIII (it would have been toward the end of the seminar on forgiveness). You seemed to me at least to take pleasure in repeating the phrase "54 million years before humans appeared on earth. 54 million years before humans appeared on earth." And I recall laughter and lightness there, all filtered through the amber and the insect cadavers, one of which was sucking the blood of the other, although they might have been making love. There was a giddy gayness emanating from beyond, way beyond, any possible sense to be made of the event's repeated trace and which was all the giddier for the traces of blood. In any case, something happened that I could want to remember. Which is why, for me, the 54-million-years-before-humans- appeared-on-earth piece of amber, with its perpetuated occupants, is a calendar that, since I would never want voluntarily to part with it, might as well be perpetual.

21. The last dizaine or décade, ten days remaining, 203 past, 163 to come. How to be done with this counting?

22. At least for the next period of ten days, I give myself the task to write (on) a different "calendar," one which does not yet count or no longer counts.

23. Another confession: in order to meet a strict deadline (the 15th of a certain month), I adopted the rule that I would write something ("anything, anything at all," said Dragan) in three or at most four days. I calculated roughly: ten periods a day, ten entries in the journal (for this will have been a journal, a record of events, and even some surprising coincidences), ten notes in an agenda. Having now arrived at the last décade, the last day of ten periods (today or tomorrow), I have little time left to stop counting.

24. The terms dizaine, décade recall the French Revolutionary calendar, which subdivided each month into 3 weeks of ten days. The term "semaine" likewise makes reference to the number 7: septimania, septimanus. (Language keeps up the count no matter what.)

25. A calendar that stopped counting, or at least stopped counting with language. Not a surface, therefore, for writing in the conventional sense, but a support all the same for the traces of events, more precisely, for the trace of an event, a singular event that took place once for the first time. But as singular, the event must also take place for the last time. The same time, the "just one time" of the event, is immediately divided, doubled, marked by the trace of a repetition. An event takes place, and immediately its days are numbered, already past from first to last, but first and last are the same, the same singular time of the event. Its unreproducible singularity is thus struck by the mark of division, divided in itself, and it is this division of the mark of singularity that makes for a trace.

26. Look anywhere, absolutely anywhere and everywhere. Everywhere there are calendars that have stopped counting, one way or another.

27. And they just look, but they do not look at anyone. That is, just as with any conventional calendar, one can never exchange a look or see eye to eye with them.

A photograph can be a calendar (and not just because many of today's cameras can automatically print the date on the negative).

For example:

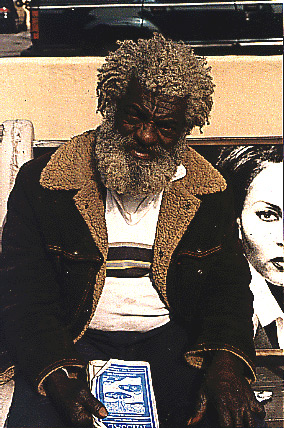

28. The photographer, my friend David Cressey, shoots photos like this all over the streets of Los Angeles, photos of lost or missing angels, of the uncounted and the non-counting. Each one is a calendar, a support for some calendar effect, the trace of a singular event.

And first of all the event that was the photograph itself. Cressey tries never to take pictures of the strangers he sees on the streets without first asking his or her permission. He is rarely refused, in part no doubt because he offers a dollar in exchange, but in part because of the manner in which he addresses his "subjects," most of whom, he says, at least appear pleased to be photographed by him. Although there is one sequence of a woman shaking her fist at the camera and a few shots of sleeping forms beneath blankets or cardboard, the vast majority of the photos are portraits, a subject sitting and often smiling for the camera.

Whether taken of smiling or irate subjects, however, every photograph shows, records, or traces this prior event of an address.

29. Not all the photos in this remarkable album are close-ups. Here is another of the same man:

For the last few days, the gaze captured in this photo, direct into the camera, has been overseeing all the marks I've been making on this calendar. However many vagaries were pursued here (and always, I might add, with pleasure; each day I've looked forward to the next dizaine), it was always the plan to end, somehow, with this photograph, and that is why I kept its gaze in my sights. From the beginning, I had the wish and the plan to reproduce this photo, show it to you, say something about it. If you like, it was my wish on this occasion of a birthday.

Now, on the 29th with only two periods remaining, everything I have come to think about this photograph could fill another month, and then, no doubt, I would have managed to say nothing but the terribly, even terrifyingly obvious. And yet, I have a strong feeling that I cannot see here something all-too-obvious and that this blind spot would be immediately exposed by anything I might venture to say. The photograph has even begun to look a little intimidating, as if it had the power to expose something in whoever looks at it. That intimidating sense does not emanate, at least not directly, from the man's expression, which is the same in both shots. In the longer shot, however, that same face and same expression is exposed to another face, which it cannot see. Or rather to half of another face. It is the right half of a famous black actress's publicity photo from a poster affixed to the backrest of the bench on which the man sits. The photo is reproduced in stark black and white and the surfaces of her cheekbones, forehead, and collar supply the whitest tones in the composition. The face has been longitudinally bisected precisely between the eyes by the photo's frame, which also passes precisely through the midpoint of her lips. Her one eye gazes at the camera, its look parallel to the man's. No doubt it is the position of this asymmetrical gaze that is intimidating: behind the man who sits in front and to the left, she sees without being seen.

But she looks, asymmetrically, at the camera and therefore at the viewer. And her monocular view is relayed back by our gaze into the man's eyes and full face, before falling again, along the incline of his bent head, into the line of sight of that single, so strangely single eye. There is in this way a constant interruption of the symmetry of the viewer's gaze, and that interruption has "itself," so to speak, taken form in the one-eyed face hovering behind the full-faced man. It is as if, with this photograph, one had been made to see that, the interruption of any gaze by another and another's. As if this condition of interruption, a condition of possibility and impossibility, could itself take form within the viewable frame, that is, assume a face, at least partially.

After long looks into all the eyes of this photo, I have seen its cruelly (?) divided face begin to dance like a hallucination, coming out from behind him and into the foreground. A hallucination in the asymmetrical mirror that is now, and as a consequence, my gaze when it looks at what appears in this photograph: the trace of a singular event.

30. I cannot see him himself at all, of course, not even with both my eyes on his. He appears here only as appearance, not just in a photograph, but also as a photograph. He himself-not the photograph but its occasion-is out of the picture no less surely than the invisible half of the actress's face. Her visible or at least indicated invisibility is working here to recall the other one, his invisible invisibility, the invisibility of the very man whose appearance, as a photo or in a photo, one is looking at. The invisible invisibility of the "subject" is always hidden in a picture and by the picture, especially portraits and even when the portrait hallucinates, as does this one, the invisible other side of the face, the face behind the face, the face no one ever sees as such.

But, of course, the photograph is also, in a most direct way, working to make visible again, to return to visibility someone who, for all his substantial presence, disappears daily before most passers-by, a fixture on a bench, less corporeal than a photograph. This is a risky thing to undertake because photography can only make visible what it makes invisible. To counter that risk, the photograph would have to induce the viewer to reverse its own process, to turn the gaze, as it were, onto the invisible face behind the face as it appears. It would have to photograph the invisible face of a soul.

If, remarkably, this photo does just that, it is because it diverts the movement of viewing through an asymmetrical eye. The soul of the other is thus allowed to hover, visibly invisible, seen but not appropriated, inappropriable.

There is at least one more detail of the photo that has kept me thinking. I mean the blue and white booklet held in his right hand and between his thighs. The lower halves of the letters of the word Missal can be read on the worn cover, the word also bisected, horizontally this time, by the frame.

The book of daily prayers, the promise of a perpetual calendar.

30+1. A last confession for this last or first day of the month of June/July. The photograph as described or as appropriated by my calendar-writing, and despite everything I have just said above about its interruption of the appropriating gaze, may be finally but another portrait of the same perpetual calendar, the (©)always(©) calendar, which is still sitting or standing nearby on the desk. In other words, a portrait, again, of "my life," mine only so to speak. This means that everything I have wanted to see or to show about the interruption of the viewer's gaze has surreptitiously been pulled back into the symmetry of a resemblance.

Just a little while ago I began to notice how many parallel, horizontal lines divided the photograph and how the man's eyes and face are set off against their light background. Well, when I attempted to draw the (©)always(©) calendar some time ago, long before I saw its resemblance with the photograph, I placed its eyes in the middle of a similar light rectangle beneath a darker one, just as in the photograph. This resemblance would be striking, I think, for anyone who could see the two side by side.

I ought to take a picture of the (©)always(©) calendar and reproduce it here for comparison. Technically, it could be done, I'm sure. But whether anyone else would see the resemblance or not is hardly a question that worries me at this point, now that I am done with counting.

But here's the real truth: the (©)always calendar(©) is the very plainest thing and I fear it may not photograph well. For now at month's end, I realize that a calendar is perpetual if it has a soul, a singular soul. To include its photograph here one would have to picture, give or take a picture of its soul. Look at (©)always(©) itself and you'll see nothing but the strictest intersecting lines, bordered spaces, some letters, and many numbers . . .

. . . and still it is beautiful,

still one wants the event to come again,

to start counting all over again,

life, in short, this short life,

perpetual life being reserved for the soul of the calendar.

All the same, you would see what I've been talking about? Still? Here then is still life's flower, still its fruit.

(Photographs by Rob Wishart)